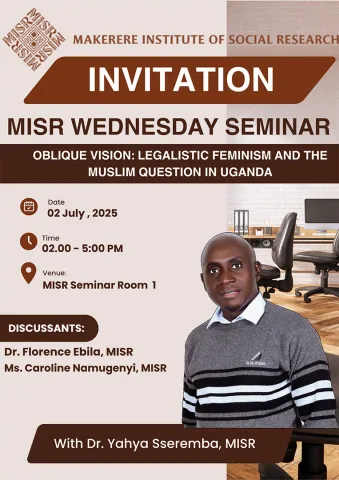

Topic:

Oblique Vision: Legalistic Feminism and the Muslim Question in Uganda

Presenter:

Dr. Yahya Sseremba

Research Fellow, MISR

Discussants:

- Dr. Florence Ebila, Lecturer, CHUSS

- Ms. Caroline Namugenyi, PhD Candidate, MISR

Venue:

Physical: MISR Seminar Room 1

Online: zoom (Click here to join)

Time: 2:00 - 5:00 PM.

Abstract

Uganda’s legal-centric feminists have formulated two disjointed and incoherent critiques of Africa’s two publics—a separate critique of the civil sphere and a separate critique of the Muslim (and customary) domain. The critique of the civil sphere is internal, seeking to change a few things here and there. But the critique of the Muslim domain has attempted to dismantle this space in general and “Mohammedan law” in particular and subject Muslim family affairs to the logic of the civil sphere. Yet, if the civil sphere and the customary (Muslim) domain are two faces of the same coin, as Mahmood Mamdani’s bifurcated state theory suggests, it means that the critique should focus on the coin itself, not merely on the faces of the coin. This chapter contextualizes the enduring fight between the Muslim community and feminist activists seeking to introduce universal family laws for all Ugandans regardless of religious or cultural identities. I locate this contestation in the making of Uganda as a Secular-Christian political association of indigenous “tribes”. This Secular-Christian and tribalist character of the Ugandan state produced a particular intersection between religion, ethnicity and gender spread over two seemingly contradictory but mutually reinforcing publics. To explain why many Muslim women—and men—have dismissed feminist campaigns seeking to override the Muslim domain, I show that these feminist initiatives have failed to locate Muslim women in the larger Muslim Question rooted in the Secular-Christian character of the postcolonial Ugandan nation state. The chapter is less interested in emphasising the intersection between gender and religion than in locating the point of this intersection in the Secular-Christian character of the postcolonial state.