MOST short and long-stay visitors to Uganda, especially from Europe and Asia, are attracted to information about something else called ‘Buganda’. Noting the closeness of the two titles, ‘Uganda and Buganda’, many such visitors wish to touch base with the country and thus seek to find ‘Buganda’ which they assume is the real or at least the foundation of the country. Of course, this ‘intellectual tourism’ is disappointed, surprised, and confused that, unlike in their countries where their history and social construction are explicit in their national identity and politics, there is no ‘Buganda’ and more so that the foundation and core of Uganda cannot be observed. But the new book by Apollo N. Makubuya is not about the damage Uganda's image suffers due to this and related misnomers; it is about the sources of these misnomers.

Overview

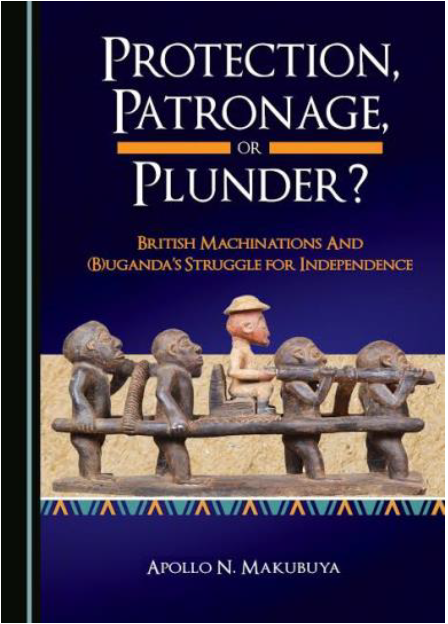

The new book by Apollo N. Makubuya (2018) with 587 pages is notably the second largest coverage of the tethering of Buganda and Uganda to the British colonial foundation, the largest such effort being by T.V. Sathyamurthy (1986) with 777 pages. There is almost no major landmark in the general history of colonial (1892-1962) and postcolonial (1962-2016) relations between Britain, Buganda, and Uganda not revisited in greater factual depth and liberal analysis in this book. Because of the comprehensive approach which thus avoids focused preset ideological trajectories and their attendant partiality, selective evidence, and limited interpretations, the book offers a free intellectual journey where the reader is not, along the way, prepared for any specific conclusions.

The message carried in the double title of the book suggests that Britain's colonial rule in Uganda was not candid and it was generally characterized by rejection. This is a new and interesting contention pitted against the official Oxford University British Africa colonial history Volumes I, II, and III (1965), and to some extent even as revisited by UNESCO Volumes I-VIII (1989-1999), of civilization, westernization, modernization, and development despite exploitation and destruction of native African history, culture, and society. The Makubuya text somehow merges the first sub-title theme of colonization and colonial rule with the second sub-title themes of coloniality, decolonization, and post-coloniality. Most such literature does not recognize the convergence and detaches colonial and postcolonial problems of Uganda's politics.

In the initial pages of the book, on the (B)Uganda toponym, the reader is struck by the Buganda and Uganda quandary, in objective and subjective terms, and the assertion that Britain is responsible for this problem. Through fusing and diffusing the titles of Buganda and Uganda, the author presents a two-pronged question: Is Uganda the same as Buganda? Is Buganda the same as Uganda? The book is limited to reflecting the genealogy (accuses Britain) of the problem of national construction, form, identity, and belonging for Buganda in Uganda.

On the mission of colonial rule in Uganda, the book makes a departure from the post-WW II 1950-1967 Makerere historians Prof Ingham, Prof. Beachey, Prof. Low and contemporary Political Scientists Prof Pratt and Prof Apter reflections of modernization against return to primitive Africa of Bataka in Uganda and Mau Mau in Kenya. The earlier British school of colonial rule (e.g. Perham) observed the civilization of Ugandans. Makubuya now debunks the paradigm of colonial protection and patronage and upholds plunder (as dispossession) of Buganda from the natives. Whereas the post-WW II European School depicted Bataka and Mau-Mau as (ignorant) evil parties in colonial history, Makubuya has presented colonial Britain as (calculating) villains and the native Bataka and Mau-Mau as (innocent) victims.

Surprisingly it is from the same primary document sources, colonial administration and policy records, that both the European Schools and Makubuya derive the two opposite positions on the motives and effects of British colonial rule on Buganda and Uganda. And besides showing that sources formerly interpreted as benevolent actually represent devious colonial rule, Makubuya introduces, from law and ethics into mainstream colonial history, the narrative of the British Government's concealment of incriminating colonial records. What is most intriguing is that Makubuya is introducing a new line of thought on colonial rule and nations like Uganda that were constructed under the regime. It is a line different from colonial modernization and underdevelopment and also distinct from the pro-colonial rule and anti-colonial rule nationalists.

It is too early to evaluate the effect of these ‘devious machinations’ and their concealment but it is likely to impact on colonial history scholarship and accepted colonial legacies and possibly even spill over into the current and future internal, within the ex-colonies, and external relations between the ex-colonies and Britain. It is not too imaginative to observe that, by expertly denigrating colonial Britain and its methods in the construction of Uganda, Makubuya has published a recipe for constitutional review over the status of Buganda. The solution is pegged to unmaking colonial ills and their legacy, and the continuing influence of Britain over Uganda.

The overall point, Makubuya stresses, is not only that there was a colonial period external actor, interest, and/or force in creating the problems of Uganda and Buganda. It is also for a foundational removal of this external colonial element in the solution and in the subsequent relations between the bona fide Uganda peoples and communities. Makubuya implies (and surprisingly only in the last sentence of the text) that the colonial-borne problem of Buganda and Uganda is sustained by Britain's economic interest in its ex-colony.

There is a marked intellectual humility as the new book introduces a fresh paradigm without directly seeking to debunk, dismantle, or even at least destabilize the different schools and discourses on British colonial rule in Buganda and Uganda. By not committing at least a chapter to the contrary discourses on colonial rule, Makubuya is perhaps contented with the parallel existence of different and thus competing perspectives. An apparent reality is that the new book is more importantly part of the campaign on the unresolved status of Buganda in (postcolonial) Uganda which is the focus of the conclusions of this intellectual journey.

More as a leader in the Buganda cultural (and political) establishment than as a scholar, Makubuya has purposely and successfully resurrected the ghost of the ‘Buganda Question’ which colonial and postcolonial Britain and successive independent Uganda Governments have (vainly) suppressed. To this effect, the text reveals that up to 1962 Buganda held a ‘Dominion’ status ("an autonomous Community within the British Empire") whereby Britain was represented by a ‘Resident’. It underlines the illegalities of acts and statutes that suspended the legitimate status of Buganda and notes that Buganda did not approve the 1996 Uganda Constitution.

The conclusions though premised mostly on the deviousness of Britain during and after colonial rule are more of a present ‘Buganda Memorandum’ of dissatisfaction with the concessions so far made under the NRM Government and the current (2018) pains and demands of Buganda within the post-1986 political dispensation and the 1996 constitutional construct of Uganda. The complaints of balkanization of Uganda's public spaces (economy, state, etc, etc) to specific ethnic units to the exclusion of Buganda and the hostility to Buganda of other Uganda ethnic units make the situation intractable. The Federal demand for Buganda is presented both as a historical right to (restore) the Kingdom of Buganda and a solution to the variety of injustices.

Finally, the book carries the message that due mainly to illegal and unethical machinations of Britain during and after colonial rule, ‘Buganda and Uganda are still at crossroads’ as stated by Mamdani in New Vision of 7/8/2009 severally cited in the text. From this book, and this is partly the Buganda Kingdom mindset, the political questions of Uganda are still hanging.

Critique

The observation that this book is more of a political statement than an academic work does not mean it has not followed a scholarly process. It is clearly based on the history method and constructivism (what Makubuya calls ‘machinations’), written records for sources and evidence with (Western) law and enlightenment ethics applied in analysis and interpretation. On the knowledge framework, the studious exercise is entirely conducted in Western epistemology, the concepts and thought process, and the language of English. The conceptual framework assumed for Uganda and Buganda is the modern Western state. The anthropology perspective for Buganda is post-WW II Western-borne social anthropology.

The first question is obviously whether such an entirely foreign intellectual package is appropriate for a critical reflection on ultimately internal Buganda and Uganda relations. However, there are many other interesting questions and debates on the approach employed in this work.

On the history method, and attendant methodologies, the first intriguing question is when does a history epoch ends and another starts, and where is the continuation from one epoch into another? In this case precolonial epoch was replaced by the colonial, which also gave way to the post-colonial. The end of one and the entry of another is a revolution. There are three Buganda (precolonial, colonial, and postcolonial) and there are two Uganda (colonial and postcolonial). To what extent, and how, are entities carried over from one epoch into another? When/where is change recognized as having occurred and when/why/where is change challenged?

The book accepts some (or even most of the) colonial Britain's constructivism of Buganda and Uganda state structures which are based on power, politics, sociology, and economy. It then rejects other constructs mainly based on legal and in some cases ethical premises. It seems that the criteria applied are not standard more so since most of the colonial era constructivism affecting Buganda is based, not on law and ethics, but on power, politics, sociology, and economy. But even the final current Buganda demand for Federal is a form of constructivism. Generally, labeling British colonial ‘constructivism’ as ‘machinations’ seems to imply that societies have no right to break, construct and reconstruct their systems.

The sourcing and reliance on only written records in studying history and other social dynamics, as in the case of this book, has been overtaken by research data and information paradigms that recognize non-written sources. In this research the sources are limited, both by choice and circumstances, to colonial Britain archives whereas the parties are Buganda, Uganda, and Britain. Even if only written sources are recognized the non-use of colonial Buganda records, as they were all destroyed during the 1979 war, weakens the exercise. However, there is definitely more about the Britain, Buganda, and Uganda problem in unwritten narratives.

The most serious defect of this work is the way it emphasized English and overlooked Luganda; the local indigenous language of the study. Sincerely, a reader who is a Muganda can shed tears at the ‘Glossary of Non-English Terms’ on pages 512-513. The language attitude shows that the author sought something in English close to that in Buganda, like a ‘King’, and then transferred or translated the English word to Luganda to mean ‘Kabaka’. In 1862 when John Speke was asked if the ‘Kabaka’ was a ‘King’ (who conquered Buganda) he was told that officially he was the one who invited/summons the Buganda Lukiiko. Speke was also informed of the meaning of Katikkiro. How can there be ‘Bataka ba Kasolya’, literally meaning the highest elders of the country (i.e. meaning land), and then write that no one was higher than the Kabaka in Buganda? Are there two highest entities in Buganda?

Finally, the most outstanding feature of this book is about the author. Mr. Apollo N. Makubuya demonstrates the highest level of Parrhesia. This, readers may be aware, is in the scholarly field the term for ‘intellectual courage’. It is not the courage and strengths of ignorance of consequences or the courage and strengths of greed; it is a daringness based on ‘intellectual rigor’ and ‘intellectual honesty’ from the available scope of sources. Few Ugandans, if any other, can write such truths about Britain, Buganda, and the Uganda Governments and leaders past and present as Apollo N. Makubuya has done in this book.

The writer is a Ph.D. Fellow at MISR, Makerere University.

The Sword is a Ugandan online periodical promoting highbrow reflections on decolonization, decolonial thought, and social justice. To support The Sword, please contact us via Twitter/X (@thesword_08) or send us an email via theswordug@gmail.com.